Copyright © 2014 Anil Prasad. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution, No Derivatives license.

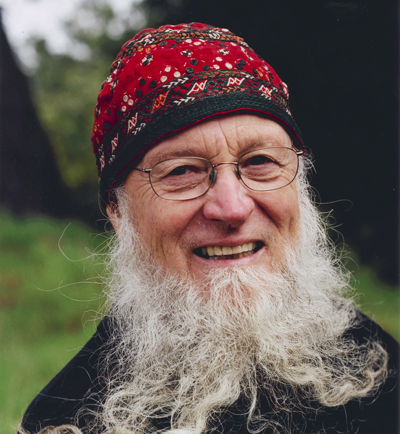

The global music community owes composer Terry Riley an enormous debt of gratitude. He pioneered the minimalism movement with his seminal 1964 composition "In C." The piece, based on interlocking, pulsating repetitive patterns, continues to influence countless musicians to this day. Riley is also one of the first to experiment with the possibilities of tape loops. His explorations began in the 1950s and played a paramount role in setting the stage for virtually everyone who integrated looping into their recordings and performances since.

His sonic footprint has stepped far beyond minimalist and avant-garde paths. Perhaps the most famous example is The Who’s “Baba O’Riley” in which Pete Townshend played organ parts inspired by Riley’s 1969 release A Rainbow in Curved Air. Gong, Soft Machine, Tangerine Dream, and Curved Air—named after Riley’s album—have also all cited him as significantly affecting their approaches.

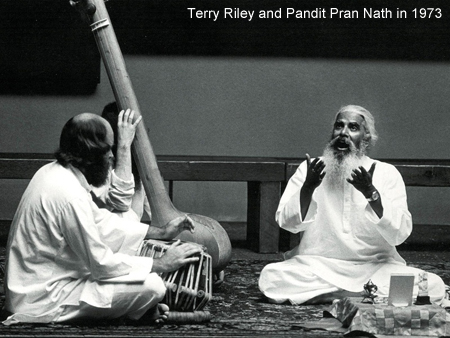

Riley’s early musical associations included working with the likes of John Cale, Pauline Oliveros, Steve Reich, Morton Subotnick, and La Monte Young during the ‘60s. But his most significant artistic relationship was with the late master Indian classical vocalist Pandit Pran Nath. Riley was Nath’s disciple and spent a great deal of time in India with him during the ‘70s, accompanying him on tabla, tambura and vocals. Riley’s immersion in the Indian raga form during this period had a profound impact on his subsequent output and musical philosophy.

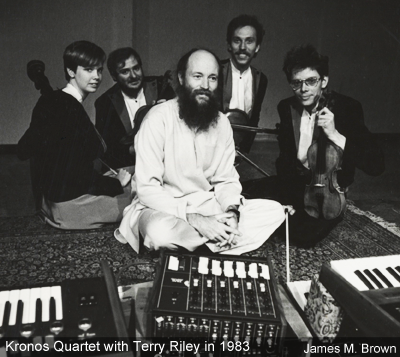

Another key partnership is his long-standing relationship with the boundary-breaking Kronos Quartet. Riley has composed more than 27 works for the string quartet since 1978, including “Sun Rings,” a NASA-commissioned multimedia piece featuring a choir, dramatic visuals and space sounds. Other highlights from his work with Kronos include Cadenza on the Night Plain, the first recorded document of their work together, and the five-quartet cycle Salome Dances for Peace—an epic suite that explores myriad genres and global sounds.

At age 79, Riley has more than two-dozen albums to his name and is accelerating his output. His most recent albums include Aleph, a long-form ambient work, and Autodreamographical Tales, a highly-personal dream diary set in a diversity of musical settings from across his career. He also has two recent, major compositions set for future release: “The Palmian Chord Ryddle” written for violinist Tracy Silverman, and “At the Royal Majestic” composed for organist Cameron Carpenter.

When I listen to your early output compared to your recent work, it feels like storytelling became more of a focus as you went along. What’s your perspective on that?

I’ve never really thought about it in those terms, but I think it’s probably true. For a long time during the ‘70s, I wasn’t writing anything down. It was pretty much just me playing my own music and improvising. When I first started writing scores again for Kronos Quartet in the late '70s, the first piece was based on Native American folklore, exploring the tales and struggles of their lives when the settlers came. “Cadenza on the Night Plain” for Kronos was driven by that. The music was influenced by the imagery. The next big piece was “Salome Dances for Peace,” and that was story-driven, too. It was supposed to be a ballet. I wrote a whole scenario for the ballet, including several pages of ideas for the dances and settings. So, again, I think the storytelling element is true. Early pieces like “In C” and “Olson III” were sonic events. They didn’t have a literary context.

How is your creative process affected when you’re meshing a narrative element with musical concepts?

The hardest thing for me when I’m starting a new project is getting it started. The big question is “What’s it going to be?” It could be related to something outside of music, and if it is, I’ll focus on what’s inspiring the music and spend time on that. It also affects me considering the structural ideas for the music I’m going to build. I’ll often just start throwing notes down on paper and seeing what comes out of the chaos. During the process, the narrative going on in my head isn’t necessarily related to the music, but it is feeding into the musical stream. It can become very strong and inspire a lot of musical ideas. It also depends on what group I’m writing for. For instance, it could be for Kronos Quartet or an orchestra. That will influence the musical direction going on as a countercurrent to the narrative. During the writing process, things can get quite intense at a certain point when the narrative is feeding into the musical ideas strongly.

Was there an element of greater meaning at work when creating your seminal ‘60s output?

I had a vision of what the music was going to be. After working with tape loops and repetition a lot, I had this idea of a musical universe emerging that I hadn’t heard before coming together. I was experimenting in the sense that I was trying a lot of approaches with what limited means I had, which were a couple of funky tape recorders. I’d watch people like John Cage work to see his approach. I would cut up tape loops without listening to the tape first. I’d just take sections of tape and put them together and found that was a very good way to work, because part of me was being fed by the unknown. But then I could work with that unknown and shape it. It laid a foundation for the way I’ve worked since. Since then, I’ve always liked to include something in the mix that has some chance operational quality about it. I like to continue surprising myself.

When you were pursuing those outcomes, how did the emotional and experimental intertwine?

For me, there always has to be an emotional element. I always work with music through a sense of feeling. The mind is involved, but things have to feel right to me. If there’s no emotional connection with what I’m doing, I drop that part. If I realize it doesn’t affect me emotionally, it’s probably not going to affect anyone else either. So yes, there has to be a little shadow of something in the process that excites me and enables me to develop the music into a bigger emotional experience.

Have you ever tried to define the qualities that are required to spur you forward?

I’ve thought about that a little bit, but it’s kind of useless because it comes up differently in every musical project I take on. It has been a lifelong mystery for me. I’ve asked myself “What is it about material that suddenly makes a composer decide this is what they want to work with?” It’s indefinable. I don’t know what it is. But I know that if it interests me, it will probably interest other people too. I first have to be really engaged and if I’m not, it goes into the file of unfinished work.

How much unfinished work do you have?

A lot. When I write a piece, I usually have five-to-10 times as much material that has been put aside. Sometimes I’ll go back to some of those pieces. There will be things I really liked but couldn’t make work in the context I was creating in. I have tubs and tubs of papers and recordings that have never made it into the public eye. If you work all day on music, and you do it a lot, stuff starts accumulating.

Do you still work all day on music?

Yes, it’s pretty much all I do. I also garden. I have a very big garden and I spend time working on it. We have a big ranch up in the Sierra and there is a lot of stuff to maintain. I do most of it myself. I still try to, even as I approach 80, even though it gets a bit hard to get around on the land.

We’re in the Pro Tools era, in which virtually any musical idea one can imagine from a technical perspective can be initiated reasonably easily. The tactile, technological puzzles you had to get your head around don’t exist in the same way anymore. How would you describe the relationship between your drive to push technology to its limits in the ‘60s and the musical possibilities that resulted?

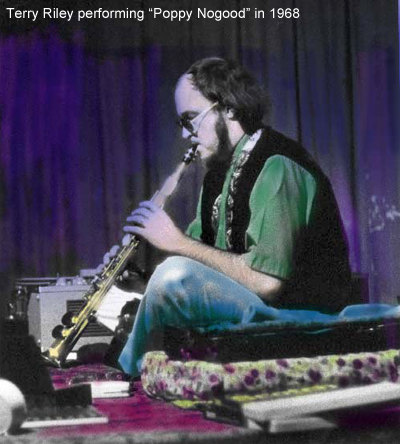

It was all driven by “What if?” principles. It wasn’t about going beyond how things were normally used. I would ask myself “What if I dragged the tape across the tape head without using the spindles or tape motors?” I was trying to find out all the different ways I could use the tape machine. It was technology with a small “t” for sure. It was a pretty tactile experience and I was getting about as much out of those things as possible. I eventually got enough money to buy a decent Revox tape recorder to use for my tape delay stuff. In concert, I would play Revox recorders live on stage. I don’t remember anybody doing that previously. I didn’t have a model for it. If there was a model for it, I probably wouldn’t have done it, because it would have been territory somebody else was into. Because the Revox machines were stereo, I could do a fair amount of switching back and forth between channels, feeding in material backwards, making pops and different sounds that were almost percussive—just from turning the knobs. I don’t think there was hardly anything I didn’t try with the Revox machines during live performances. I would have two things going on. I was always playing the saxophone or fooling around with the knobs on the recorders at the same time. So, pieces like “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band” were developed that way live, before I ever took them into the studio.

Where did the name “Poppy Nogood” emerge from?

My daughter when she was little would call me Poppy. Sometimes, she would get angry with me if I did something that displeased her and she’d shout “You’re no good!” So, I started using that name. The tape loop piece “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band” was about the idea of one person making music, with the phantom band being the loops and mirror images of myself produced on tape. I also thought “If you’re no good, you’ve got nowhere to go but up.” [laughs]

What would you do when something went wrong with the tape machines in concert?

Did they ever. [laughs] Again, I had wonderful models around me like John Cage. I realized that the best thing to do when something goes wrong is to make something out of it. It was the same thing when playing piano. If I hit a wrong note, it wasn’t actually a wrong note, but rather a new direction to go in. If you take that note and play it 100 times, it’s not a wrong note anymore. It becomes part of the piece. I used the same idea with technology. Sometimes a big feedback thing would happen. When that occurred, I would drop the saxophone and start working with the feedback. If something like that happens, the music is trying to tell you something. It’s telling you to work with what’s going on instead of stopping. If you stop, you’re interrupting the messages that are coming into you. You’re blocking information. So, I like the idea that there aren’t mistakes and that things are always happening as they should.

Can you recall a tape disaster that occurred when everything went wrong?

Yeah, during one of the early performances in Saint-Paul de Vence at the Maeght Foundation. Aimé Maeght was holding the first Festival Nuits De La Fondation Maeght in 1970. Sun Ra, Albert Ayler, and Pandit Pran Nath performed at it. I was playing with David Rosenbloom and my wife Anne, who was on a kind of autoharp. I was performing a version of “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band” and the tape recorders caught on fire. That was the most dramatic concert moment I’ve had. The tape machines burst into flames. They had to get fire extinguishers to put them out.

I didn’t know tape machines could burst into flames.

I didn’t either! [laughs] It was great. It was a real event for the audience, complete with smoke and fire. It lasted about 15 minutes. After that disruption, I brought the solo saxophone out of the smoke from the fire. I think everyone thought it was part of the performance.

So, it was your Hendrix moment.

[laughs] Yeah, it was—without me trying for it to be.

What can you tell me about the earliest origins of the open tape loop approach you pioneered?

I was working with Anna Halprin’s dance company in Marin County in 1962, creating music for her along with La Monte Young. We worked together with her. She had a better tape recorder than I did, as well as a lot of other sound-making devices and percussion instruments at her studio. It was a good live sound environment. So, I began recording my first sounds over there. This was around the time I got my first recorder, which was a Wollensak. It was a little mono tape recorder. They didn’t even have stereo yet, but I could do sound-on-sound, which meant I could record over the sounds I had made before.

As I said, Anna had a better recorder. So, I would record the initial sounds over at her studio. She also had an old piano against the wall with the strings and soundboard exposed. It was a great echo machine, because there’s no damper on the strings. So, if I touched them, they would ring until they died out. Anna had a bunch of steel ball bearings and we’d roll them across the dance floor and slam them into the inside of the piano with the soundboard and strings. It would make an amazing sound. I’d take recordings of those home and try to put them sound-on-sound onto my little Wollensak.

The first piece I did was called “Concerto for Two Pianos and Five Tape Recorders.” I borrowed four more Wollensaks and La Monte Young and I played it for the first time in Berkeley, using these sounds I made in Anna’s studio. For the performance, instead of putting things sound-on-sound, I put a different reel into each machine. It was a really primitive way of getting five tracks. We played pianos live to that. That was the first thing I remember doing.

There’s a recording of the performance, though it’s very strange. It’s on the Music for The Gift album on the Elision Fields label. It’s from a live KPFA broadcast, narrated by Glen Glasow. Glen talks over the piece because he doesn’t know the concert’s starting. It’s hilarious. He’s saying things like “I don’t know. It looks like they’re doing something onstage. We better tune in down there.” Then we’d stop playing for awhile. Next, he’d say “I guess the concert hasn’t really started,” but you can hear the piece underneath it. After awhile, he stops talking and you can hear four minutes of the piece. [laughs]

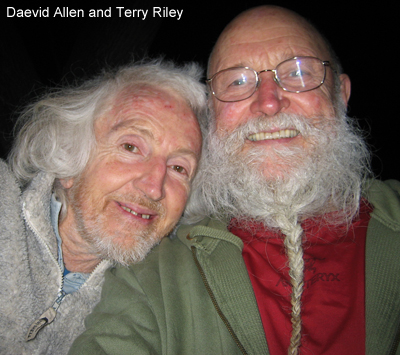

Between 1962 and 1963, you were living in Paris and often hanging out with Daevid Allen. Reflect on those days.

Before I went to Paris, I was living in San Francisco on Portrero Hill. When I was a student at UC Berkeley, my next-door neighbor went to Paris ahead of me. When I finished my work at UC Berkeley and got my MA in composition, I couldn’t get a Prix de Paris. I applied for it, but never won. I was playing ragtime piano in San Francisco in those days and saving all my money. My wife was teaching and eventually we amassed enough money to go to Europe for a couple of years. When I got to Paris, I hung out with the next-door neighbor from San Francisco, who was a friend of Daevid Allen’s. At that time in Paris, Daevid was delivering the Herald Tribune newspaper. He had a route that went through the Paris Opera and up through Pigalle.

One night, Daevid flipped out and threw all the newspapers all over the street and was just done with it. I said “I could use that gig.” I thought it would be fun. So, I sold newspapers. I’d start out at the Paris Opera and I still remember being at the opera the night Marilyn Monroe died in August 1962. I immediately sold out of all my papers. I didn’t even have to go to Place Pigalle that night. Eventually, I got other jobs and got out of that newspaper gig. I started playing at Fred Payne’s Artists’ Bar, which used to be on my paper route. The bar had been there since the ‘30s. Fred was a very old, English expat who had this bar full of young French prostitutes for businessmen. So, I would go in and play piano for them as they had their fun. Sometimes, they would close the bar at night and I’d play piano all night while the guys were frolicking with the women. I liked playing at Fred’s, because it actually developed some of my improvisational skills. Nobody cared what I played. Sometimes I’d do a long, extended improv and Fred would say “That doesn’t sound like music.” [laughs] But it was a place to freely experiment in front of an audience. Then out of that, I got another job playing floor shows in France. It launched me into making some money. I got some decent jobs out of it.

So, Allen being disgruntled with a newspaper delivery job proved to be a pivotal moment in your career.

Yeah, it did. [laughs] Daevid and I remained friends through that whole period in Paris. I got Daevid into tape loops. I played him this stuff I had done in San Francisco with Anna Halprin like “Mescaline Mix” and pieces like that. Daevid got really interested in that and started doing a lot of stuff with tape loops. We used to jam a lot together in Paris. I’d also hang out on his houseboat on the Seine. It was very funky. He probably got it for $50 or cheaper. It was tied up to a quai and was a very small, one-room space. He lived there the whole time I was in Paris. We had mutual friends down at The Beat Hotel in Paris. We’d go down there a lot. We’d meet people like Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs there. Our cultural life at the time involved going from the houseboat to The Beat Hotel. We ran into many interesting people.

Daevid was a much hipper guy than me. He was more into the Beat and pre-hippie scenes. I was a straight UC Berkeley graduate who experimented a lot with weird music, so we had that connection. I educated him about musical ideas and he showed me things about the free bohemian life you could lead in Paris. I really liked Daevid’s fantasy drawings, poems, and the funny Australian language elements he’d use. It was captivating for me. He was very influential on me. He showed me a new kind of life, even though his was chaos. It was pretty easy for Daevid to flip over into the other side, but he could always keep it together enough to keep going. This was all pre-Soft Machine and Gong. I remember Robert Wyatt came over to the houseboat one time and I got to jam with him. He was playing one of those Dizzy Gillespie-style trumpets with the bell going up. I thought he was a trumpet player when I met him, and he was, I guess, back then. Robert is so talented. He could do anything. I last saw Daevid when he came to visit me when I had a place in Richmond, California, five years ago. He stayed with us there twice. He’s an extraordinarily gifted guy. Gong is also one of my favorite bands. It was one of the places that rock ended up that was very vital.

How did your life change when you became a disciple of Pandit Pran Nath in 1970?

It was a big change. It was similar to taking on a religion and knowing that you really have to believe in it in order to have it work for you. You have to really envelop yourself in it and that’s what happened when I started studying with Pandit Pran Nath. It was under the general heading of raga, but actually, he was a musical universe of his own that was separate to what was going on in raga. For me, here was a person who was doing music that was headed towards the same direction I was going in, but in a different way and coming from a very old tradition he was still connected to. Who he was and how he could express himself so freely through raga created a real kinship. I also felt he was a much older soul than I was and I surrendered to that. I kind of let raga be my main focus for most of the ‘70s, although I was still doing concerts to keep that side of things going. I was concentrating more on raga because I realized that if I didn’t give it six hours a day or more then I wasn’t going to get anywhere with it.

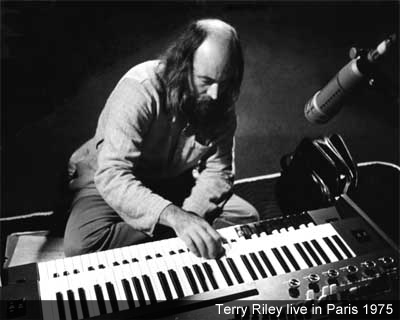

I wasn’t writing any music then, but I was going to Europe five-to-10 times a year doing solo organ concerts. My music was very well-received there and they kept asking me to come back, especially to France, Italy, Scandinavia, and Germany. I quit playing saxophone and was developing solo piano performances that were very much informed by my raga studies. I was becoming more melodic as I learned the intricacies of the raga and how I could sustain a really long form that way. I had already worked with that a bit with my pieces of the ‘60s. My music was already shaded that way, but it got stronger through my work with Pandit Pran Nath in terms of how I could build long, modal, sustained forms, because that is what raga is.

Did the purpose of music alter for you during that period?

No, but I think things intensified for me. Music was still touching the same nodes in my being, but it was intensifying. I was getting lit up in a much stronger way. That’s why I stayed with it. I realized it was something I was meant to do.

What went through your mind when he asked you to become his disciple?

I had been listening to his music a lot during the time I lived in New York between 1967 and 1968. Shyam Bhatnagar had brought these recordings over of Pandit Pran Nath that he made on a cheap tape recorder. The album was called Earth Groove. It’s badly recorded and produced, but has beautiful singing. La Monte Young and I were listening to a lot of Indian music in those days, but when the Pandit Pran Nath recordings came over, we both thought “This is something important.” I would always play the Pandit Pran Nath recordings while I did yoga in those days. I was getting more and more into the magic of what he weaved with his music. La Monte then arranged for Pandit Pran Nath to come to the USA. He asked if I could arrange for a concert for him at Mills College in Oakland, California. I did, so Pandit Pran Nath, La Monte, and Marian Zazeela came and stayed with us at our loft in North Beach. We did the concert at Mills and the day of the concert, he asked me to become his disciple. I didn’t even know what it meant, but I knew La Monte and Marian had done it and became his disciples.

I wasn’t sure what kind of contract I was getting into, so I was a little worried. I talked to La Monte and Marian who said “This will be the best thing you have ever done.” But I had the worries of “Am I going to become someone’s slave? Am I going to be brainwashed?” It turned out to be a really significant move. When you become a disciple under the traditions of India, you essentially become a family member and take care of each other in whichever way you can. It was a way of learning music. I had a lot of music teachers in my life, but they were much more casual. This was intense. I’d have music lessons at 3 am or in the afternoon. I wouldn’t even call them music lessons in a conventional sense. He would just start singing and that was the lesson for me—sitting beside someone that powerful as a musician who could go into this space and start singing amazing ragas. He was allowing me to be there. Otherwise, nobody could do that. He didn’t want that many people around. So, most of my training was the association—just being around him and inspired. Sometimes he would sing to me and ask me to sing back.

Reflect on your personal relationship with Pandit Pran Nath.

He was my best friend. We were very close, and yet it wasn’t a friendship in which we spent hours and hours talking. He didn’t talk much. We would sit together and go for long walks. I would take him to concerts by people like Philip Glass who he hadn’t heard. I was introducing him to a lot of Western music and he was taking me around to all of these incredible Indian musicians and saints—people I would never have been able to sit with or experience otherwise. I went to Dehradun and lived in a temple with him, with the swami from there. It was like living in a world I couldn’t have imagined for myself. He opened up many doors for me.

Describe how the element of spirituality influenced your time with him.

He was much more religious in a traditional way than I’ve ever been. He was more of a Sufi, influenced by both Islam and Hinduism. He would practice both. He would do his poojas in the afternoon but he would also have a lot of Sufi elements in his life. A lot of the music was Sufi ghazals. He would say “I’m a Hindu in the morning and a Muslim at night.” There are other examples of saints like Sai Baba in India that no-one could figure out in terms of whether they were Hindu or Muslim, because they knew both intimately. They would teach their Muslim disciples about Islam and their Hindu disciples about Hinduism. I think he was more in that tradition.

I got absorbed into things because I was going to a lot of holy spots and shrines, putting my head down on the base of tombs and saying prayers. I did all of that because I wanted to feel what it was like to do that, to see if anything could be awakened, and things did. You can’t do stuff like that without there being some real experiences. I think I’m still trying to figure all that stuff out, even at this late stage of my life. I’m still looking at everything as being a big mystery that I don’t know. I’m comfortable with not knowing. My firm faith is that I don’t know. I feel very strongly that’s a good faith. It’s a good path.

During your immersion in the raga form, you had largely evolved away from relying on conventional notation.

Yes, but I wasn’t doing that much notation anyway, if you look at the scores I produced in the ‘60s. So, I was already thinking that notation wasn’t going to be a big issue for me. I got much more into that later in life. I still feel like it's not the right way to go, even though I do it. It’s one way to go. You can write a big, composed score, with everyone being told what to do using notation. You can create a musical event that you couldn’t create any other way. But I don’t like telling people what to do in general. It’s not my most comfortable musical activity.

David Harrington, the leader of Kronos Quartet, said when he engaged you to work with the group in 1978, part of the arrangement was that you would create notated scores. What was it like for you to revisit that world so deeply?

It was a change. It was kind of nostalgic in a way. In the early ‘60s, when I was at UC Berkeley, I was writing music. I remember what the experience was like of having a pencil in my hand and spending a few hours trying to create something on paper. At the beginning, I thought it was interesting. I was able to look at ideas in more detail. I started by writing down stuff I was improvising. When I started notating them, I thought about other ways things could be done. Notation is a slow motion experience. I could see elements in the music that had bypassed me during improvisation. I realized that through writing, I had more time to consider the many directions that a musical event could go, whereas in improvisation, you’re in the moment and the music goes where it’s taking you.

When I started working with Kronos initially, I was thinking about doing something in between notated and non-notated music for them—something in which they could have little ideas to build on, sketched out on little pieces of paper and handed to them. We worked on that for an hour and David just turned to me and said “You know, I think we need something totally written out for the way we work.” [laughs] So, that was a crucial point in our working together. It forced me into making all the compositional decisions.

Your works outside of Kronos since 1978 have seen you work in less conventional notation formats, such as The Harp of New Albion from 1986.

Oh, there’s hardly anything for that. [laughs] The Harp of New Albion is tuned in just intonation. I sketched the different scales the sections were derived from. I’d select certain note sets out of the tuning of the piece to build a section on. I would write those down, which would be just like any just intonation scale with maybe a couple of patterns I was basing that section on, such as a melodic motif. If I handed that to almost any another pianist, he wouldn’t know what to do with it. There are certain pianists who know what to do, but for most people, there’s not enough notational information. For me, that form of notation is something I use so I won’t forget things. It’s a way to jot down musical ideas. If I don’t think I’m going to forget something, then I don’t bother.

Tell me about your creative process as it stands today.

I do a lot of improvising and if something emerges that’s pretty involved and really interesting to me, and I don’t want to take the time to write it down, I’ll record it and transcribe it later. Sometimes, I’ll get an idea in my dreams and I’ll get up and write it down. I keep a little notebook for dream music. In my dreams, it’s usually a good friend playing the music and I’m jealous that they had these wonderful ideas. [laughs] After I write the music out, I’ll sometimes experiment with a notational program on the computer. I’ll throw out a lot of stuff in the process. It’s like a sculptor taking a bunch of clay and materials, combining them, and then pruning things down into some kind of organized form.

What software do you use?

At the moment, I use Sibelius. For years, I used Logic and Notator, which goes way back. Logic was the main one for awhile because it was really good for sequencing. For “Sun Rings,” written for Kronos, it was a really good program to use because it could handle both notation and audio samples.

You’ve directed an incredible diversity of musicians across your career. Describe your collaborative approach.

I usually work with people because I like their work. The best thing for me is when you collaborate with someone because you like what they’re doing and don’t have to get in their way. If you talk to people I work with, they’ll tell you I don’t give them any directions. I usually provide examples of what I’m interested in. I’ll play something and figure that through musical communication, they’ll get the idea of what I’m driving at. I work with special types of people that are really comfortable with that approach. A lot of times, they’ll use their own note paper and pencil, and write down the notes for themselves. A lot of times, I don’t give them anything. It’s all done through playing.

What makes someone an ideal collaborator for you?

I have to really like the way the musician treats the music. I like improvisers who see things in the material beyond what I’ve seen, or see things in a different way than I do. I like it when people add something to my perspective. Essentially, I’m a soloist and it’s a little bit of a problem sometimes because I play too much. I provide the whole idea of what I’m thinking to collaborators. When I work with other musicians, I try to tone down things or calm myself down, so I give them more room, and don’t play everything. That’s been a big learning curve for me. For instance, when I work with George Brooks, Tracy Silverman, Krishna Bhatt, or my son Gyan, I know that these are all very good improvisers and composers themselves. I like them to take the ideas and do something with them. I don’t want them to do the same thing I’m doing with the ideas. I’m always happy when they find their own role in the work. I’m essentially laying out a musical idea that I find interesting. I want them to take my melody or rhythmic cycle and then see what they discover within it.

Despite your significant influence on the rock world, you never pursued that universe outside of The Church of Anthrax album with John Cale. Why didn’t you explore rock in more depth?

It doesn’t feel like a good fit for me. I could be a rock musician. Some people think that’s what I’m doing. I’m not that knowledgeable about the rock world and what’s going on today, but when I hear certain things, I think “That’s not that different from what I’m doing.” But if you’re talking about rock with guitars, drums and a backbeat, that would be too confining for me. However, when I play with Gyan and I’m on synthesizers, sometimes it’s very rocky and we get into real grooves. We’ve played a few festivals like All Tomorrow’s Parties in which we’re considered rock musicians. What we do fits right in with those festivals.

How did The Church of Anthrax collaboration come about and what are your memories of what you and Cale were seeking to explore?

I had worked with John in the Theater of General Music with La Monte Young. When John left the group to join The Velvet Underground, we continued our association. Columbia signed John and me around the same time. We ended up both working with John McClure, the executive producer at CBS. He was a wonderful, incredible visionary producer who co-produced "Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band" along with Dave Behrman. He told me that although A Rainbow in Curved Air was a great idea, it wouldn’t have much of an audience, so I should do something that would capture more interest. John had produced Stravinsky and Harry Partsch albums for CBS, so he was coming from the classical world, but he also saw where rock was going at the time. He felt classical musicians should be involved on the rock side more. So, he talked to John Cale and I about doing something together. He knew we had played together previously with La Monte, so he felt it would be a good fit. John and I both liked the idea, though we weren’t disciplined enough to put together any plan for the recording session. We played together once or twice at someone’s house before we went into the studio. I think maybe we had one tune that we used on that album that we tried to play before we went in to make it. Otherwise, it was created during those sessions. There weren’t many sessions, perhaps two or three.

How do you look back at the end result?

It was amazingly good given the preparation that went into it. It was largely created on the spot, using two drummers, Bobby Gregg and Bobby Colomby, who were wonderful musicians. They were solid, but I think it was kind of strange for me because I hadn’t been playing with drummers previously. So, to have drummers as the driving force behind what we were doing was interesting. I remember, one of the pieces we did was in 14 beats and told them “Here’s how the pattern goes.” They said “Oh, we don’t want to play in 14. That’s too complicated.” [laughs] So, they just ended up playing in 4/4, which was interesting for me. I realized it was a better solution to the problem, because we had these two different times going on at the same time. So, it felt like rock in 4/4, but something else like Indian music where we were in 14.

John Cale and I had a lot of disagreements about the album, including the way it should sound and the way the material should go. During the last mixing session, John started feeding in a lot of extra guitar tracks over what we had done. That started to obscure some of my keyboard work that I thought should be heard. We had a disagreement about that, so I stopped going to the mixing sessions and they mixed it without me. It all fell apart and I ended up leaving New York because of it. I felt like I was starting to have a nervous breakdown over this album, so I moved back to California. I was living in New York for three-and-half years until then. John Cale and John McClure finished the album.

Over time, I’ve grown to like what they did, but I think it would have sounded good with my vision, too. I think it probably became more of a rock album because John was a rock musician and really understood what had to be done to make the record rock a little more strongly.

We tried to do a Church of Anthrax II in the late ‘80s or early ‘90s. I flew back to New York for some sessions with John. We hadn’t seen each other for a long time. As it turned out, he didn’t want to play on it. He wanted to produce me and have it be my album. I realized that wasn’t what I wanted to do. I wanted to do a collaborative thing and work together like we did the first time, because I did really like playing with him. He really is a good musical collaborator and force. But I didn’t want to be produced by him. I didn’t need a producer. So, we didn’t end up doing it.

Tell me about your relationship with Don Cherry in the ‘70s.

I didn’t see Don that much, but we ran into each other once in awhile. We first played together in Scandinavia, when Don was living in Sweden. I went over and met him there. We did one recording in Copenhagen just before I went to India in 1970. It was bootlegged and is available out there. That was the earliest example of us playing together. I thought it was a very unsuccessful session. We went into it maybe smoking too much dope. [laughs] I don’t feel we connected very well. Don wasn’t very happy either. But other people thought the music was great, so you never know. The other time we played together was in Cologne in 1975. I was staying at Mary Bauermeister’s house. She was the ex-wife of Karlheinz Stockhausen. Don was staying there a lot. A German producer asked us to do a concert in Cologne that was recorded for radio and it’s out there too. I don’t know who got hold of the tapes from the radio, but the recording sounds fairly decent. Again, we didn’t plan anything. The best recording from those sessions is when I’m playing “Persian Surgery Dervishes” and Don is playing along, creating a countercurrent for it.

What are your recollections of Cherry on both a musical and personal level?

I liked the fact that Don was the kind of guy who was playing something all the time. He’d walk down the street playing the flute. He was almost like a street musician, yet he had this professional career playing with Ornette Coleman and many other great jazz musicians. But he was also very loose. He just wanted to play music all the time and had a free spirit that I liked a lot.

I only met him a handful of times. I remember in New York, he would come around at the time his daughter Neneh was born. He lived around the corner from me. I had a loft on Grand Street and we hung out a bit. We must have played some music that day. I don’t remember if we had anything specific in mind. When I went to Sweden to do “Olson III” with a choir featuring kids from the Nacka School of Music, Don was living in Stockholm then. He came out and heard the piece, and really liked it. This was after In C, but had the flavor of In C. Don thought it was an interesting musical direction and talked to me a lot about it, what I was doing, and how I arrived at it. He was very curious. It made an impact on him. The concert we did in Cologne also made an impact on him, but we didn’t follow it up with anything. The legend is sometimes bigger than reality.

There was another connection I had with him, which is his deep interest in Indian music. He knew I had been with Pandit Pran Nath by the time I was in Cologne. He had a session with his group Multikulti in Cologne and he asked me to come over. I tuned the tamburas and gave him some input about Indian classical music. Of course, I was pretty new to it all, too. But I knew a little more than they did. Later, he went to India too and studied with some of the Dhrupad Dagar musicians.

I understand you and Edgar Froese mutually influenced each other’s creative paths. What can you tell me about that?

I got a fellowship to work for DAAD, the German Academic Exchange Service, in the ‘70s. They gave grants to artists to come to Berlin. During my time there, I met Edgar Froese, who invited me to dinner. He said I was one of the reasons he started Tangerine Dream. He said they would come to my concerts in Berlin at the Meta-Music festivals held there. They were some of the very first, big world music festivals I was aware of happening. Others like Michael Hoenig and younger rock musicians came to those Meta-Music concerts, too. I think my kind of performance—which I never considered space music—was something unique for them. It gave them an idea of what a rock performance could be like for electronic musicians.

While I was in Berlin, Edgar said to me “You’re playing electric organ. You’d probably like playing a synthesizer.” So, he loaned me his Korg synthesizer and I got my first experience working with one. This was around 1978. After that, I got my first synthesizers, which were the Sequential Circuits Prophets. My technical assistant at the time, Chester Wood, also worked for Sequential. So, he had the synthesizers designed so they could be tuned in just intonation. I started playing two Prophets instead of electric organs after that.

Around that time, you also began working with Kronos Quartet. What inspired you to first work with the group?

I really liked David Harrington and when I started talking to him in 1978, I got caught up in his infectious enthusiasm for trying to get me to write music for them. I was really excited by their playing. When I first heard the audition tapes they sent, it was pretty amazing to hear these young players with the kind of energy they were putting out as a string quartet. So, that’s what got me started. Also, David was very persistent in keeping after me to put some notes down on paper.

Tell me about your attraction to the string quartet format.

I first wrote a string quartet in 1960 when I was a student at UC Berkeley. It was 20 years later that I wrote my next one for Kronos Quartet. But I was always very keen on the format from the beginning. I studied the Bartók quintets in school. I really learned a lot from what he did with string writing. It’s a really good, very manageable form. It has enough people to get an interesting dialog and texture going, contrapuntally. It covers a nice range, although string quartets never had enough bass for me. I always wanted to have a bass player in there, too. The great thing about string quartets is the players are kind of like family. They work really well as a unit, so you can write things that let them use those talents of association and intuition—all the things they’ve developed together as a group. String quartets are typically very interested in fine-tuning the music, so you can get some very polished ideas happening with them.

Harrington said your composition “The Wheel” represented the point at which you collectively arrived at a defining sound for your partnership. Describe it for me.

That piece was like a simple jazz ballad. It was the first piece in which we stressed not having any vibrato. It has a sound like ancient music—a non-vibrato sound with a more austere feeling. I understand why David felt it was important. It gave them a way to play together that maybe they hadn’t considered before. It enabled them to make a new kind of sound they started developing a lot. It was an almost disembodied sound that I really like to have in string quartets sometimes. The full vibrato is a very expressive sound on a string. If you take that away, you have another area to work in that draws the listener in more. The listener has to lean into the sound to really get the experience, whereas with a big vibrato, the listener can just sit back and bathe in it. The non-vibrato sound was an aesthetic thing I was interested in getting to. We worked on it a lot together. We explored it during rehearsals.

Later on, I also gave them things to do with just intonation. They were prepared to deal with that, because it already takes a non-vibrato sound to effectively produce the intervals related to it. In rehearsals, we would also go over passages and talk about them. I would sing passages to them and turn passages into exercises. This approach wasn’t purely coming from me, because it’s the way Kronos works. They go really deep into the details in the work they do. Sometimes, they’ll work for hours on just fine-tuning a chord. There were a lot of rehearsals when I was kind of worried they wouldn’t learn a piece in time because they delved so deeply into the details so close to a performance date. I thought “When will they get to the rest of the music?” [laughs] But the key to a good performance is dissecting some parts of the piece. It’s part of the string quartet tradition. It’s how four people come together to play a piece as a single voice. We kind of expanded that a little bit.

How has your collaborative approach evolved across 35 years working together?

It feels like we’ve built a dialog and understanding together. When I bring a new score to them now, they already have a very good feeling about what I want. It isn’t like we have to start from scratch every time, because we’ve already worked out some of the aesthetic ideas in prior works. It’s only when I bring something in that’s quite different that we have to spend more time on trying to get it right. From the beginning, the mechanics of the five us together have worked well. Though the person in the cello seat has changed over the years, we still very much work as we always did. I like to give them as much time and freedom as necessary before I actually enter into things to see what they will hear in the music. A lot of times when they learn a piece without me, they come up with things I didn’t consider that are really valuable contributions. Sometimes they’ll make a slight change in tempo or they’ll play something with a different stringing effect than I considered. Perhaps they’ll play something slower than I thought it would go. As they get into the finer details in terms of the interactions between the four of them, they sometimes surprise me in a positive way with something I hadn’t envisioned.

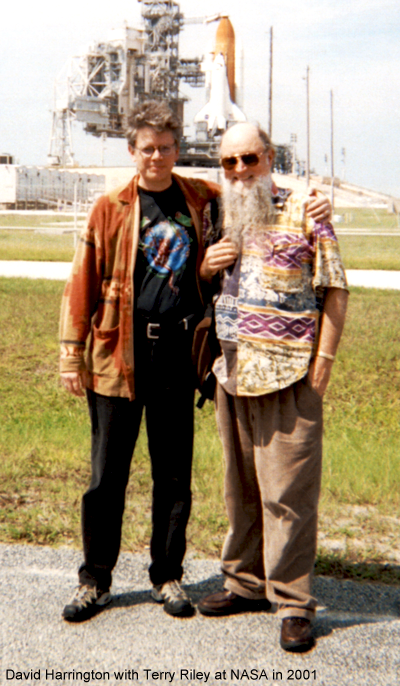

Describe the challenge of writing “Sun Rings” for Kronos.

It was a long process of even getting to the point of writing “Sun Rings.” David and I went to Cape Kennedy and spent a few days just getting into the mood. We saw a space shuttle launch and toured around there, getting a feeling for the place. So, that inspired both of us. Then we came back and I started writing in late August 2001. But then 9/11 happened and it kind of stopped me in my tracks, because I realized we were now going to go to war. The mood in the United States was very ugly to me. People were raising flags and the extreme kind of false patriotism emerging was very disturbing. I actually stopped writing for awhile. It took awhile to get back into working on "Sun Rings." When I came back to it, I wanted to have my feelings about 9/11 as part of the piece. It became a piece more about understanding and compassion than about space exploration. I thought it had to have one message about how we human beings have to grow before we take our culture out into space. So, I decided to add a choir to reflect the human element, in addition to Kronos and the space sounds.

From the start, the piece afforded an opportunity that went beyond a string quartet. It was a piece that involved a team, including Willie Williams, who was very important when it came to putting together the visuals. I also had an assistant named David Dvorin who worked a lot on modifying the space sounds so I could use them more as instruments. He had a lot of technical expertise with computers. It was the first time in a long time that I had been involved in a team effort like that. I was writing the music, but a lot more had to happen to really bring it all together. Larry Neff also did some amazing things with live visuals. There was a lot of positive energy. It seemed every time somebody would come in with an idea, everybody would get it and be on the same page with it.

Another major piece you worked on for Kronos is 1998's “Requiem for Adam.” Reflect on writing such a personal piece for Harrington and the group.

There was a lot of loss for Kronos around that time. Adam Harrington was David's son. David and I are very close friends. We had spent a lot of time together with our families. Adam and my son Gyan were both born on the same day, a year apart, so we had a deep connection. I was with Adam the day before he died on Easter Sunday. We were at David’s house Saturday just having fun, joking around. And the next day, when I got the news that Adam had suddenly died, I almost immediately thought something has to happen here. It was too tragic. I had already written a requiem for Mario Moruzzi, who was the stillborn baby of Joan Jeanrenaud. I wrote a requiem for Hank Dutt’s partner Kevin Freeman, who died of complications from AIDS, just before that. “Requiem for Adam” was a large-scale work and the most personal, because Gyan and I were so close to Adam and David. It was a strange thing to write in a way, because it puts David through so much pain to play the piece. It was a double-edged sword. David got a sort of release out of it. After the first premiere, I remember we just grabbed each other and cried for about 10 minutes. It’s the most powerful thing we’ve ever done together.

Tell me about translating your very personal feelings about Adam Harrington into the composition.

David sent me a lot of music Adam loved, including punk rock and other dark and edgy stuff—music that young people like. I wanted to have some of that in the music, but I also wanted to have a feeling of ascent—a spirit turning into light. So, I tried to get that sound in the piece, with the quartet going into the high register with harmonics. That part of the piece became very ethereal and light. I tried to develop the moment to point to certain areas. During "Cortejo Fúnebre en el Monte Diablo,” which is the funeral march, I made it scary and loud. The opening to it is especially a shock. It first hits very loudly and clangorously. I wanted to communicate the shock of what was really happening, because Adam died really suddenly. This has been criticized by a lot of the press for not fitting into the movement, because it comes in and jolts you when you hear the sound. To me, that’s what it was. It was the heart of the piece. It was the death moment.

I remember as I was showing David the unfinished quartet, he was totally in agreement with the direction I was moving in. The main thing that was always hanging in the air is that this was not just playing another piece. I was always aware of that not just for David, but all the quartet members. This piece was something that was being put in the place of the life of Adam Harrington as a kind of monument that pays tribute to his life.

How is your personal spirituality reflected in the piece?

In "Cortejo Fúnebre en el Monte Diablo," my model for the music, though maybe nobody hears that in it, is the New Orleans funeral march, where people march behind the cortege with trombones, trumpets and cymbals, creating music which isn’t our ordinary concept of church music. The first movement, "Ascending the Heaven Ladder," has all the music rising and it ties all of the elements of the piece together, which turn up in different contexts as it progresses. As for my spirituality, it’s kind of homegrown. I don’t belong to any organized religion, but I’ve been very involved with Eastern thought and ragas. In general, that has taught me to be open and embrace the mystery of our existence, and see what develops in life. I want that expressed in all the music I do, but I especially wanted it in this piece.

Tell me about the recent piece you wrote for Kronos’ 40th anniversary.

It’s called “The Serquent Risadome,” and it’s a 10-minute piece. David commissioned it as part of several short works in the 10-12 minute range. I did something that was very spontaneous and written very fast. I think it’s a very cohesive work and I’m grateful it came together so quickly. It has a lot of different, related sections. I wanted the piece to express the joy I’ve had working with Kronos and I think that’s in there. It’s a very high-energy piece, but it also has some poignant moments, so it touches on a lot of our work together.

Describe the personal connection you have to the group and its mission.

Kronos has taught me an awful lot. One of the things I felt was amazing about Kronos is that they were able to be very critical of each other and never take any of that personally. That was a big lesson for me, because I’ve been in a lot of bands and worked with a lot of musicians, and when you say to somebody “Hey, you’re out of tune there,” they might stomp off the stage. With Kronos, everything is always on a very professional and deep level. They’re always thinking about the right resolution of whatever problem might come up. The fact that they would spend hours getting a tempo right or interval in tune, and keep focused on that one element, was another big lesson for me in group rehearsals.

I’ve learned so much about writing quartets by being with them. I’m not a string player, so coming in and working with them was just like being at school. I learned so many ways one can use a bow, the different vectors of the bow, and even how changing bows can create a different sound. I also learned the different ways a quartet can be organized. It could be one soloist with three people accompanying it, or it can be four people in a very dense, contrapuntal dialog. There are so many ways of setting things up. Every piece I wrote for Kronos, and even other pieces I’d hear them play of other composers, was really educational. Also, the kind of humanity reflected in the group is important. The group has always been about family. Everyone that comes into the work gets absorbed into the Kronos family. So, it’s as much about people as it is about music. That’s something that appeals to me a lot.

Tell me about the dream diaries that informed your Autodreamographical Tales album.

Staten Island’s New American Radio, an NPR show, commissioned people to do half-hour sound pieces. I did one and decided to use a dream journal I was writing in 1996 as the basis for the radio story. I wasn’t sure what I was going to do with it. I had recently bought some ADAT recorders and as the first project to use those, I composed this piece on them in my studio. It was pretty simple. I just read stories of the dreams I liked the best. At some point, the stories gave me ideas about songs to write. I interspersed the stories with the music. It was a multifaceted project that used the dreams to launch me into it.

When I recorded the stories and listened back right away, I’d think of a musical hook that should go with them. The dreams were also different, so it was easy to come up with unique ideas for each one. One is called “The Miracle,” which is about a dream I had about a miracle when I was in Italy. Another dream was about meeting an orchestra conductor who was performing some of my work in London, so I wrote an orchestra-like piece for it. There was also a very hilarious dream about Pandit Pran Nath. I used tamburas on it. It’s almost Indian music, but not really. It has a non-descript atmosphere. I wanted to include the component ideas into the pieces, so the album isn’t an autobiography—it’s an autodreamography. The title seemed appropriate to me and nobody had used it before that I know of.

It feels like one of the more important works in your discography. Do you agree?

I do. It really is a theatrical piece, even though it’s a studio recording. It could have been staged. It’s an important piece to me because I allowed myself certain freedoms to create in a way that I don’t when I’m writing an orchestral or concert piece. The pieces are very personal, given the way I read them. You get a better idea of who I am when you hear them.

People think of you as an extremely serious individual, yet there’s a lot of humor on the album.

That’s a misconception. [laughs] I don’t think of myself that way at all. I’m serious in that I’m very focused on my work. I work all the time. But humor is what makes the universe bearable. It makes life bearable, too. One of the most profound ways to understand the mystery of who we are is through humor. Life is playing tricks on you all the time. You have to just laugh at it.

I don’t usually make overt jokes in music. Autodreamographical Tales is humorous, but it’s a kind of wry humor. I don’t do Spike Jones-like things, although I like Spike Jones. I grew up on his stuff as a kid and I thought he was a master at what he did. But I can’t think of any examples where I’ve actually done anything like that.

Tell me about the making of Aleph, your 2012 solo ambient album.

John Zorn was curating a festival at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco, which had just opened at the time. For the opening, John invited artists to create works for it. I was one of them. I went down there, looked at the space, talked to the director, and agreed to do it. But something happened in my life or in their process. We lost communication and my time to submit the piece came and went, even though I had already done the piece. So, it was sitting in my studio. I called John and said “I did the piece for the project, but I never heard back from them. Now, I see that it’s over.” John said “Oh good! Great man. Let’s put it out on the Tzadik label. Send it to me!” [laughs]

Aleph was going to run on an endless loop at the museum. It has very minimal material. I recorded it one single session very late at night. I hadn’t done an extended modal improv like that for a long time. I thought it was a good revisiting of the territory of Persian Surgery Dervishes and some of the other stuff I did in the ‘70s.

You’ve worked with your son Gyan in great depth in recent years. Tell me about the musical telepathy that you experience when you work together.

Telepathy is the right word. It’s very easy to play with him because it’s like an extension of myself. He’s a wonderful collaborator in that he’s able to totally focus on what’s going on in the moment and in the music. Sometimes he anticipates things and there’s so much unison with what I’m doing. I don’t know how he can think what I’m thinking at the same time I do. I have that more with him than anyone I’ve ever worked with. I enjoy working with him so much because of that. It’s a great gift to work with him as a guitarist accompanying ideas I come up with. My only regret in a certain sense is I don’t have the same abilities he does. He’s a wonderful composer and I would like to be able to do the same thing for his music, but his music is too hard for me to play. It’s more complex than mine is. So, I’m aiming to learn one of his pieces very well and play it so I can see how things feel on the other shoe.

When Gyan was growing up, did he benefit from being around the legendary musicians you’ve been associated with?

He did. At one point, when I saw he had amazing musical talent as a young kid, I tried to teach him piano and that was a total disaster. He couldn’t accept me as a teacher, so I stopped. But he was always there listening when I was rehearsing in the studio. He didn’t do too much traveling with me, but we had a lot of musicians coming to the ranch where we lived. I didn’t notice how much he was paying attention, but suddenly at one point when he was still fairly young, I was doing a concert with Krishna Bhatt and we took Gyan along. I said “Krishna, why don’t we have Gyan bring his guitar and see what happens?” Gyan sat in with us and I could see he was able to command his space on the stage. He wasn’t worried about playing with Krishna, who is a great master sitarist. Gyan didn’t feel intimidated by that. He played the guitar with confidence. After that, we started inviting him to perform at shows with George Brooks. Gyan also has a trio with Tracy Silverman. He’s been part of my performing life ever since.

One of your more recent works is “The Palmian Chord Ryddle” written for Tracy Silverman. Describe what makes it unique.

A few years ago, I wrote that concerto for electric violin which was premiered in Nashville in 2010. It was written specifically for Tracy because he’s developed an instrument which has six strings and goes down almost to F, a fourth above a typical cello’s lowest string. So, it has a full cello-like upper violin range. It’s a magnificent-sounding instrument. Tracy has worked on the technological development of this instrument for maybe 15 years and continues to refine it. He’s so integrated in his playing and has created something unique. You just don’t hear anything like this instrument out there. The closest person I can think of is Jean-Luc Ponty, but Tracy has taken it into a different area. I was planning for a long time to write something for Tracy and then there was a commission involving the Nashville Symphony. Tracy lives in Nashville and wanted to do it there as a premiere. It went on tour and ended up at Carnegie Hall. I was really conscious of Tracy and his instrument as the center of the orchestra. It’s a real concerto in that sense. The orchestral music develops out of the sound of his instrument, and there’s a dialog between the instrument and orchestra. I think it’s one of my most successful orchestra pieces. It really worked.

Tracy is such a great performer. It’s a very complicated piece and he memorized it for the performance. He’s a really great jazz and country musician too. He has so many skills. He’s a Julliard graduate with a classical background, and he was able to get the orchestra to swing in a unique way. He gave them cues on how to play the music, because there’s a lot of back and forth between the solo instrument and orchestra. He taught them phrasing that couldn’t have happened with any other musician.

The piece is called “The Palmian Chord Ryddle” because it came to me in a dream, in which I was designing a chord for the opening of the concerto. I didn’t know what mode I was writing in. The dream said to me “You’re writing in the Palmian mode.” At that time, I had written a lot of the piece, but didn’t have a title for it. So, the title came kind of late and was an identification of the mode of the piece.

Another major new composition is your concerto “At the Royal Majestic” for Cameron Carpenter, another younger virtuoso. Tell me about the making of it.

It’s a concerto for a very large orchestra and pipe organ. It’s essentially like having two orchestras. The pipe organ we used when we premiered it at Disney Hall in Los Angeles had 6,500 pipes. It came about after I played a couple of solo concerts at Disney Hall on that organ. They decided at Disney that I should write a concerto for myself. I thought that I’m not really an organist and that I’d like to write it for someone who is a real virtuoso on it and the pedals. They suggested Cameron Carpenter, who I didn’t know about at the time. He’s one of the most extraordinary virtuosos on the organ that has probably ever lived. There are almost unlimited possibilities for what he can do on it. He has a kind of rock, kinetic energy when he’s playing that’s very physical.

The organ isn’t a physical instrument. You can’t make it louder by hitting it harder, but Cameron gives that impression through the way he plays. He really slams into the keys. He’s a very dynamic performer and also an incredible musical mind. He’s a very good composer and improviser, too. He has all the skills you can imagine and I felt really lucky to have him playing this piece. I wrote it with him in mind. I wanted it to be something that would be very challenging for any organist.

It’s a 35-minute work in three movements. I broke the orchestra up into pipes. I looked at it as opposing pipes to the organ pipes. So, there’s three piccolos, three flutes, six bassoons, two bass clarinets, six trumpets, two trombones, and two tubas. There’s a lot of interplay between the organ pipes and those instruments. Of course, you have the full string complement and five percussionists as well. It’s much different from any concerto that’s ever been written for organ—and there aren’t that many as it is.

It’s a major, dynamic work with a lot of tempo and meter changes. It could only be played by somebody who’s going to rehearse it a lot. It’s a challenge for an orchestra to play. They have to be fleet-footed to make it work with such big forces. It’s like getting an elephant to walk a tightrope. We had John Adams conduct the premiere in Los Angeles. It was also recently played in Berlin, conducted by Giancarlo Guerrero, who also conducted “The Palmian Chord Ryddle.” It really came to life during that performance and he did a magnificent job with it. He created a minor miracle by getting the orchestra to dance like they did. They were all really swinging. It was good to hear it as I imagined it. Giancarlo is going to have it performed and recorded in Nashville in 2016, so it will come out, along with “The Palmian Chord Ryddle,” which has already been recorded and is ready to go.

You’ve seen many phases of the music industry come and go. What are your thoughts on the complexities of surviving as a musician in this day and age?

It’s interesting. When I was in New York and signed my contract with CBS in the ‘60s, they only had stereo. When I went to record In C, they wheeled in the first four-track machine. For A Rainbow in Curved Air, I think I was the first project on the eight-track machine. Those were interesting jumps to witness. It’s fascinating to go into digital and experience infinite tracks. If someone had told me about that in the ‘50s, I wouldn’t have believed it. Everything that has happened in technology is incredible.

So, things are changing fast in many ways, but not always for the positive. The intellectual property rights of artists have become a very grey area. Now, people seem to be able to use the material of other artists for sampling or even releasing entire albums under their labels without securing the rights. This seems to be happening more and more. I don’t think anyone knows how that’s going to play out in terms of musicians being able to make an income. Just 10 years ago, things were fairly clear. You had performance rights organizations like BMI or ASCAP tracking and collecting income for musicians pretty reliably. Now, the tracking has become complex. A lot of potential income doesn’t get recorded. A lot of musicians I know are very pessimistic. I think other things can take the place of the old system, but the truth is musicians are going to have to figure out other ways to supplement their incomes. They’ve always managed to do it. Being a musician has always been a survival field.

Occasionally, it must hit you that your music has fundamentally altered the way many look at and understand music. How do you internalize that fact?

I’m surprised by that, because I came into this as an untrained musician without conservatory training. Even when I was at UC Berkeley in the masters program, I resisted learning traditional Western music. So, there are so many musicians that have so many skills I don’t have, and I really admire them. I’m surprised that people have been influenced by what I’ve done because I consider myself somewhat of a self-taught amateur. So, why are they influenced? But then, I do see it as well. It started happening right away as soon as I wrote “In C.” There was a wave of people who started doing things like it. I felt threatened because I thought “Well, I won’t have any identity now, because everyone can do this.” I thought “In C” was something unique and felt something would be lost with everyone else doing similar things. But what happened is I realized that there was a lot more from where “In C” came. It might not be as influential, but there’s a lot more I was able to keep doing. So, when I do look back, I see that maybe there is a certain identity in my music and that the pieces have been different enough to keep an interest in the public. I’m grateful that people have enjoyed my work and been moved by it.

You’re approaching the age of 80. What does that number mean to you?

It’s a little unreal. It doesn't have any real meaning, though. It’s an imaginary boundary. The main thing is that I’ve recently felt if I’m going to do anything, it’s now or never. When I was younger, I thought I’d do a project 10 years from now, or I’d revise a piece later. Now, it’s about today or tomorrow. Every day I wake up realizing I’m at the tail end. Pandit Pran Nath would say “Now, only the tail of the dog is wagging” when he described his own career when he was at the end. So, I’m in the tail of the dog period and I still have a lot of things I want to do. I feel a sense of urgency to do some projects I feel should be worked on and finished up. It’s not so much about new projects, but about older ones I want to work on.

For instance, there’s my opera The Saint Adolf Ring, a major two-hour work based on the life of Adolf Woelfli, a Swiss artist who suffered from schizophrenia and created his entire output over 35 years while confined to a mental institution. It was a kind of guerilla theater opera. I was basically the only musician, and there was Sally Davis, who was the actress, singer and dancer, and John Deaderick, who played Woelfli. Mikhail Graham did all the tech work, including throwing samples into the piece. He was a very important part of the sound. Lulu Ezekiel did all the sets. We really worked hard on putting the show together and we had nine performances worldwide. It never went anywhere after that. We got the show to a very high level of performance, but I never wrote a score for it. There isn’t a single note of music for everything I played. But the pieces are all composed and are in my head. I performed them every night, every time. I feel I should document them. The first thing I’m going to do is put out a CD of the last performance from Bern, Switzerland, which is pretty well-recorded and should be available as a document. Many people ask me about the opera, but don’t know what it is and haven’t seen it, so the recording should be available. I also want to write out the score so it can be performed by somebody else in the future.

I’ve got a lot of other things in my sketchbook that are basic ideas I want to work on. I don’t know how to describe them to anyone else, but they are works I mainly perform solo that I haven’t notated yet. That’s been the big problem. Because I’m an improviser, I can improvise works without a score.

Many artists at your age are content to rest on their laurels. Describe the forward momentum that continues to propel you.

Every day I get up and want to do music. New ideas keep coming to me. I can’t repress them. They’re just there. If I was to rest on my laurels, what would I do? I wouldn’t have any way to pass my time. I don’t like television. I don’t like most of the pastimes people have. I can’t garden all day long. I don’t have the physical energy for that. So, music is a great pastime. The music doesn't let me languish. It’s the one thing in life I feel totally in love with.

Website: Terry Riley

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento